The Gist

Machine learning is frequently used across business and marketing, allowing chatbots to be more lifelike or companies to offer products that better-fit someone’s shopping habits. Ping Zhang, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical informatics and computer science at the Ohio State University, asked the question, “Why not use ML for medicine?” This led them to uncovering great, untapped potential in ML that could reshape how serious ailments are treated in the future.

At AKASA, we’re always thinking about how we can use machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to better healthcare operations and improve the healthcare industry overall.

Research is a crucial part of what we do. Part of our team is dedicated to ML research, looking exclusively for ways to improve our AI and automation efforts. This dedicated research team then partners with our ML and core engineering teams to implement their latest developments into our product for customers. We’re developing and publishing on state-of-art machine learning services from end-to-end.

But, AI and ML are still largely emerging fields, and we want to ensure we’re always pushing the limits of what these technologies can do.

A big part of our research is hearing from other engineers and AI and ML experts, and seeing what kind of advancements they’re working on.

As part of our ongoing technical learning series, we recently brought in Ping Zhang, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical informatics and computer science at the Ohio State University (OSU), to share updates on his new research. He focuses on machine learning, data mining, causal inference, and their applications to biomedical informatics and computational medicine.

At OSU, he heads up his lab, AIMed (aka Artificial Intelligence in Medicine). Zhang and his team wanted to use AI and machine learning to do the seemingly impossible: extract usable medical data through causal inference and machine learning to discern which potential drug treatments have the best outcome for patients of varying severity.

“Dr. Zhang’s recent research suggests another potential to improve human health by using real-world patient data. Patient data is something we have a lot of. We’re always looking for ways to get more out of existing data for improving people’s lives, and Dr. Zhang’s research serves as a great example of what’s possible with this data and machine learning.”

~ Byung-Hak Kim, AI Technology Lead at AKASA

Using Machine Learning to Extract Usable Information from Real-World Patient Data

When you have a headache, you take Tylenol or Ibuprofen. These medicines have worked for you in the past, so why would you try something else?

Clinical care is similar. Physicians typically have a singular goal: help patients feel better. Oftentimes this means using whatever treatment is most popular or powerful. This approach isn’t always wrong, as the treatment often works. But, what if there was a better treatment available, that was overlooked?

This is the question that drove Zhang and his team to embark on the following experiment.

The Goal

The process of treating a disease is complex and often lengthy, expensive, and full of trial and error. Zhang and his team at OSU believe this is a problem AI and predictive modeling can solve.

Using predictive modeling, Zhang and his team aimed to better predict which drugs physicians should use at which stage of treatment for patients with particular diseases of varying severity.

(Just because Tylenol works for your headache, doesn’t mean it’s the best solution, right?)

“If we look at data as a slice, this slice can include nursing notes, medication and physician notes, diagnosis and the medical images, lab tests, and any reports. There’s a lot of information within real word patient data. Based on this type and amount of data, we can do a lot of machine learning data management tasks.”

~ Ping Zhang, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Informatics and Computer Science at Ohio State University

The Challenge

Randomized control trials (RCT) are essential in an experiment, especially one with stakes as high as medicine. But, in the medical world, RCT is costly, difficult to come by, and time-consuming to acquire through first-hand experimentation. On top of this, there are various confounding factors in any medical trial.

- If you want RCT in the medical world, you need approval from the appropriate agencies, willing participants that fit a certain criteria, medical professionals to run and supervise the trials, and the time it takes to run a proper trial. This is often upwards of two years in the medical world. Zhang and his team could afford neither the financial cost, nor the time.

- Anytime you’re looking at a medical case, you have multiple factors that influence the patient outcome: age, gender, overall health, treatment used, and so on. And then you have the confounding factor of disease severity before treatment. Without RCT, these confounding factors could present an issue with accuracy.

Deep learning and AI only improve over time when the right, accurate foundation is put in place. Without proper RCT data and with so many confounding factors in place, the margin for error was seemingly massive.

But Zhang and his collaborators found a solution.

The Solution

Because RCT was out of the question, they needed to take a different approach to get data that was as close to usable as RCT as possible. This required some out-of-the-box thinking and a multi-pronged approach.

RCT data wasn’t available, but observational, real-world evidence (RWE) was plentiful: electronic medical records, insurance claims data, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, CVS prescription data, and so on.

Clinical decisions often depend on the severity of a patient’s illness. The above information, when matched up and examined, could provide that information. Sampled across thousands of records, the team could essentially create their own RCT using the RWE.

But, while clinical decisions are often dependent on disease severity, physicians often prescribe the better drug regardless. This will typically result in the patient getting better, but if there’s an alternative drug that’s more successful, shouldn’t physicians use that?

This is where the researchers thought of drug repurposing, the act of using a drug that was originally created for one thing, to treat something else.

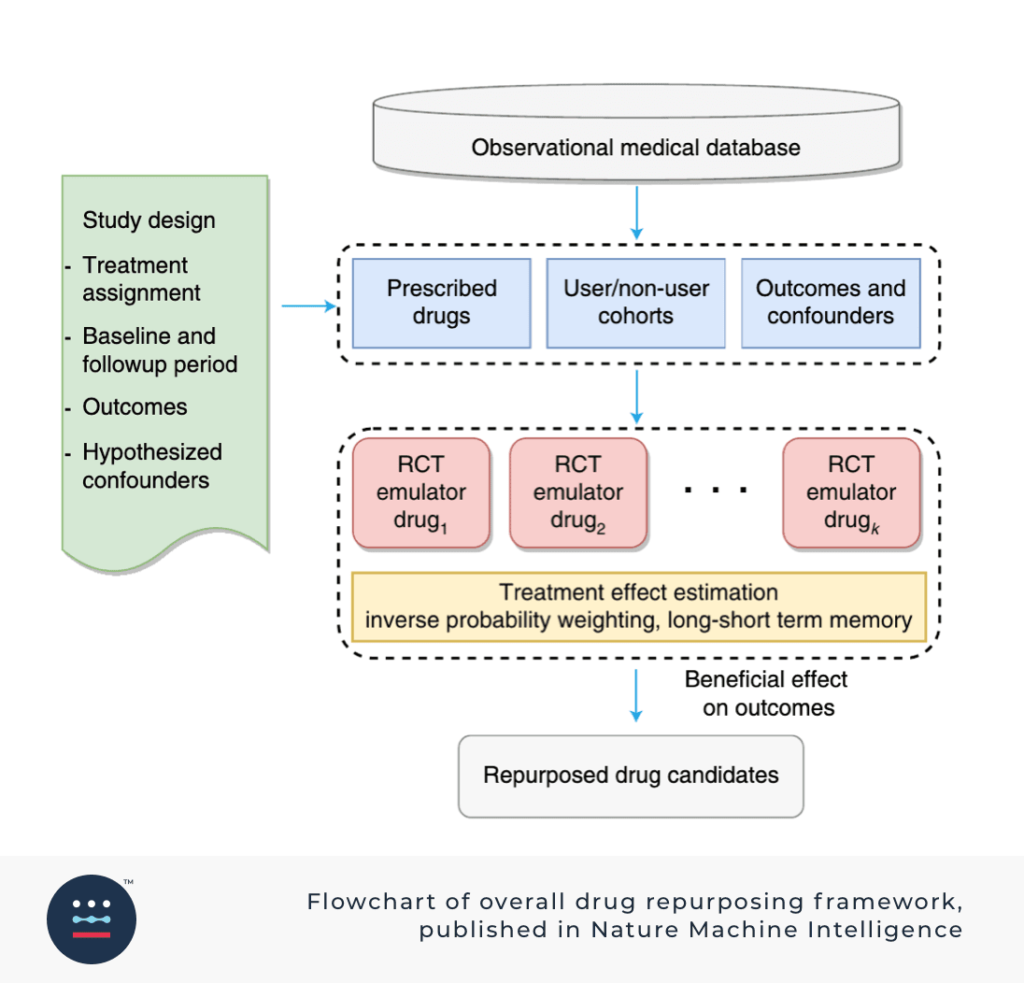

Zhang’s team used deep learning and causal inference by emulating RCTs through use of the observational data mentioned above. RCT data can take years to amass. They didn’t have that kind of time, but they did have years of observational data. The team divided their mass amount of data into disease cohorts based on severity, patient intake, and drugs prescribed.

Using a deep learning framework, LSTM, they modeled electronic medical records or RCT using the aforementioned observational data, divided by cohorts.

In the end, Zhang and his team determined their methods weren’t better than existing methods, but complementary to preclinical methods. This is because the work fully focused on clinical data, making it a great supplement to the preclinical work being done by other experts.

Why This Research Matters

There’s obvious potential with this work. Over time this could become a way to accurately model and predict what drugs will provide the best outcome, which drugs can physicians repurpose, and which drugs ultimately save the most lives.

Beyond the medical benefits of the research, this kind of technology showcases the untapped potential of deep learning and AI.

They managed to find potential drug candidates that reduce the risks of heart failure and strokes — without proper RCT data. If the team’s methodology was applied in a clinical setting to RCT and with even more funding, imagine the potential?

Thinking beyond the medical world, could engineers in other fields apply this methodolgy to other areas?

Imagine AI processing various materials to determine which type of metal is best suited for a construction project or vehicle, deep learning that analyzes layouts of factories to streamline pathways for efficiency and safety, and so on.

AKASA and the Future of Healthcare Operations Automation

We’re building automation that’s tailor-fit to streamline processes for healthcare operations. Even a few years ago, the idea of fully automating entire portions of healthcare operations sounded like a pipe dream.

Today, we’re able to automate the work of full-time healthcare operations employees, automating medical coding with better accuracy than humans, and streamlining most of the claims process — and we’re only getting better.

If you’re interested in helping us push the limits of AI and machine learning, we’re always looking for top talent and brilliant minds.

Join the AKASA Engineering Team Today